Rules are meant to bring predictability to an area so that individuals can reliably make value judgments and figure out what is good and what is bad for the group. At their best, rules set up clear incentives that allow for group flourishing while bringing stability to individuals. The clear line between rules and “to rule,” i.e. governance, is too on the nose to say much about. What is interesting though is how rules are indirectly related to governance. As Rivika Galchen notes in “Why We Obey Rules”, the exceptions to the rules are the primary region of governance.1

Here, we’ll build on the work done in the Yak Collective governance primer and develop further intuition about the nature of the structures and processes in place that constitute “rules.” We also model the nature of rules within organizations, focusing on three dimensions: thickness, alignment, and velocity.

Thickness refers to the amount of context and judgment needed to apply a rule. As discussed in “Why We Obey Rules,” thin rules apply to all cases uniformly and require minimal context to provide clarity in a given situation. Thickness comes from the amount of context and judgment required to decide if the rule has been violated and assess the corresponding punishment. Perhaps counterintuitively, thick rules can be fairly short. For example, the golden rule “do unto others…” is very thick and its context-free application is guaranteed to cause trouble. On the other hand, thin rules are often lengthy but can be applied globally with minimal context. In the ideal state, a thin rule can be applied programmatically with only a few variables supplied — think the right-hand rule in electromagnetic or an attendance rule at school. In computational law (see “The Legacy of Hammurabi”2 for more details), perfectly thin, computable rules are the platonic ideal.

A dimension explored in the Yak Collective governance primer that makes sense to employ in rules analysis is alignment: are the participants under common rule adversarial or do they mostly trust each other and share common information to achieve unified goals?

A final dimension to consider is the velocity the organization needs to function. Is this a well-oiled bureaucracy trying to keep a large nation functioning for the next hundred years? Or is this a quick startup that must move quickly to make payroll next quarter? Does the direction the organization takes matter at all (velocity is a vector after all) or is spiraling but not dying an option that would work? This is particularly interesting as we come out of multiple years of long-term planning hopelessly mired in changing circumstances.

We now have thickness, alignment, and velocity as three dimensions with which to analyze rules. We are making some assumptions here. While slower organizations (similar to slower organisms) tend to be larger, we won’t be taking the size of the organization into account.

A goal for organizations that is of particular interest is longevity. How can the organization keep moving even if key personnel are missing? How can the goals be achieved even if resourcing is halved. The focus is on resiliency and the ability to keep playing the game. The mascot here is the bristlecone pine, able to withstand decades of drought, heat waves, and cold snaps.

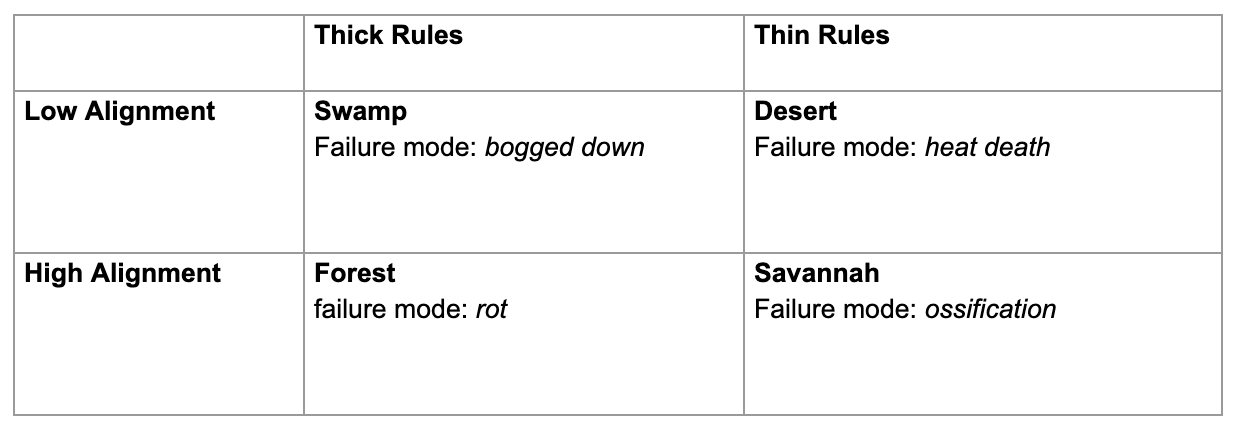

Map of the landscape

Here’s a preliminary analysis of the four regimes a slow velocity, longevity-focused organization may find itself in. I’ve taken a stab at assigning each regime to a landscape to help you get a visceral feel for how it might feel when you’re in it.

Swamp: Thick Rules, Low Alignment

Combining thick rules that require human judgment with low alignment can quickly lead to factions forming. Individuals in these organizations don’t trust each other and the lack of common knowledge renders most forms of top-down governance powerless. The vibe here is slow, dangerous progress, much like wading through a swamp. The failure mode is getting so bogged down with in-fighting there isn’t time for much else.

Desert: Thin Rules, Low Alignment

Thin rules imply some level of common knowledge across an organization so not all is lost just because there are adversarial factions in the group. Having the ability to trust decision making goes a long way to improving conditions over the Swamp quadrant so while there may be lack of trust between individuals, there is a common framework for decision making and more importantly, for updating the rules as we move along. The danger with adversarial rules is twofold. The most common danger is rules not getting updated with changing times, thus getting stale and out of date. The more pernicious danger is rules getting updated too quickly, causing confusion, churn, and eventually heat death due to too much entropy. Much like the desert, this region has clear, but dangerous rules — if it gets too hot or you run out of water before getting to the next oasis, you’re dead.

Forest: Thick Rules, High Alignment

As soon as we bring high alignment into the picture, a lot of early foibles that low alignment orgs can succumb to are no longer concerns. If there are thick rules but everyone mostly trusts each other and the decision makers, the organization is mostly in the clear. Problems can occur when these trusted leaders are replaced or become less trustworthy. Like an old growth forest, organizations like these are susceptible to rot triggered by outside pests.

Savannah: Thin Rules, High Alignment

The Savannah quadrant is interesting because at the outset I expected it to be the preferred one. However, on closer inspection, I think this might be a region in which to exercise caution. The high trust, high alignment is good initially and a lot of good rules may programmatically apply. The concern though will be the ability of the group to have enough flexibility to change given changing circumstances. If there’s sufficiently high alignment, the invariable edge cases of the rules will go unhandled, leading to worse events down the road. The elephants of the savannah provide a clue to what behavior is needed here. They have long memories so follow well-trodden paths but still give leadership opportunities to a matriarch to make adjustments as needed to hit watering holes at the appropriate time for the herd to survive.

What to do

Seeing it laid out like this, my opinion is you want to nudge the organization to be in the healthy forest of the Thick Rules, High Alignment quadrant. It’s a stable equilibrium while the other quadrants are either more vulnerable to high impact events or to succumbing to factions. Competent people can make any quadrant work but since the goal is longevity, the best quadrant to be in is the one with lowest need for competence.

Contrast the pygmy shrew with the bristlecone pine. For a high-speed organism like the pygmy shrew, the game is surviving to the next meal, with its quick heartbeat and rhythm of life, while the slow-growing bristlecone pine has evolved strategies that enable it to play the long, long game.

We’re left with many novel threads to chase down here. How can an organization complete the most goals in the least amount of time, eking out enough surplus to keep the crank turning? Thin rules may be quicker to infer results from than thick rules, though they are likely to be wrong in unsatisfying ways. Which region may work best for this goal? How should rules be designed and optimized for speed?

Footnotes

-

“Why Do We Obey Rules” by Rivika Galchen is an inquiry into the nature of rules and the conditions that are conducive to the success or failures of various forms of rules based on a directly relevant book, Rules: A Short History of What We Live By by Lorraine Daston and based on peculiar metaphors from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in the Wonderland known for its seemingly nonsensical world with no rules.

Daston theorizes rules as thick or thin, paradigmatic or algorithmic, failures or exceptions, justified with historical anecdotes. The idea of a model with which something is to be compared but which is not meant to be identical is discussed in the context of the ancient Greek word for rule, kanon, and the Latin word regula. The former was associated with a physical unit of measurement; the latter along with a similar physical measurement was also connected to a model by which others were measured metaphorically.

Lastly, Galchen claims that Carl Schmitt’s idea of sovereignty in terms of “the power to decide on the exception” could lead to authoritarianism when a cataclysm occurs. And this is contrasted with the various encounters in Alice’s Wonderland where the nonsense or the lack of rules on the surface is nested with apparent careful logical precision by Lewis Carroll who himself was a mathematician. ↩

-

The Legacy of Hammurabi by Michael Genesereth considers the spread of legal codification of rules a public good. Early attempts at legal codification were simple; it was sufficient merely to codify and promulgate the desired rules. Modern laws, however, are complex and difficult to understand even for the initiated. Genesereth has many examples of this, including a particularly humorous one comparing the Declaration of Independence (~1K words) to the laws for the sale of cabbages (~27K words).

The article claims this is a tractable information technology problem and looks to computational law, the branch of legal informatics concerned with automated legal reasoning and automated compliance management. In this respect, the principle technology innovation discussed is machine-readable translation. Genesereth compares three different approaches to converting legislation to actionable rules: logic-based programming emerges as the goldilocks technology, traditional programming being too difficult to maintain and hard to explain and natural-language processing too ambiguous to use. ↩